As England and the US prepare to meet on 12 June for their first game of the World Cup in South Africa, the BBC’s Kevin Connolly reflects on the two sides’ last World Cup encounter, in 1950.

It is still the benchmark against which all subsequent sporting surprises should be assessed.

On the world’s biggest stage, a squad of amateur and semi-professional footballers from the United States defeated England’s football aristocracy.

To get a sense of what it meant back then, imagine a British student baseball team defeating the New York Yankees or a pub cricket club defeating the Australian test cricket side.

The US lineup comprised a postman, a mill worker, and, appropriately for England, a funeral ician.

One or two of their players were unable to go to host country Brazil due to a lack of available time off work.

The English Football Association (FA) had never bothered to enter prior World Cup competitions; England had developed football, and if other groups of foreigners wanted to amuse themselves by claiming to be world champions, they were free to do so.

Everyone knew England was the world’s best team.

And the 1950 squad was fairly excellent as well; gathering at the airport for the newsreel cameras, they were confident and calm, which isn’t surprising given that most of their fellow countrymen imagined they were going to Brazil to collect the cup rather than compete for it.

There was the captain, Billy Wright, who gave a modest but confident statement about wanting to win the cup, and he had some of England’s greatest players at his disposal, including Stan Mortensen, Stanley Matthews, and Tom Finney.

War veterans

The World Cup of 1950 was not the global tournament that South Africa will host in 2010.

It was a bright spot in the dreary austerity of post-World War II Brazil, but it looked hopelessly remote elsewhere.

Some of the eligible teams, such as India, withdrew due to the high cost of coming so far to play, while others saved money by sailing rather than flying to the competition.

Because it was so far from Europe, radio coverage was poor at best, and most fans would only see a few minutes of newsreel footage from the games, which were typically aired days later.

The English and American teams had one thing in common: they were made up of rugged young men who had lost the greatest years of their playing careers due to the war.

Stan Mortensen and Wilf Mannion fought on the English side, while Frank Borghi and Frank “Pee Wee” Wallace were decorated warriors on the American side.

They varied from the cosseted stars of the modern game in other ways as well.

The England stars made more, but not much more, than the spectators who paid to see them every week, while the American squad was on such a short budget that they didn’t know until the last minute whether they’d be getting new shirts for the tournament.

few month, I traveled to rural Pennsylvania to meet Walter Bahr, one of the few survivors of a game that is still a source of pride for American soccer fans and a cause of constant annoyance for English football.

Walter and his squad were well aware that England were the favourites.

“Our goal was probably to keep the score respectable,” I heard him say. “We knew they were more prepared, coached, managed, and in greater shape.

“We went in as utter underdogs. I don’t think any of us expected to win.”

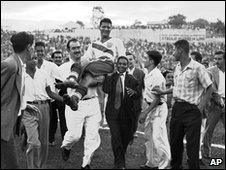

The essential story of the game isn’t really disputed. England dominated possession, hit the woodwork and might have had a penalty but on the counter-attack the Haitian-born American Joe Gaetjens deflected a long range shot from Walter Bahr past Bert Williams and into the English net.

In a newspaper cutting, Walter and I found a quote from Williams which implies a rather grudging English reaction even after all these years.

The Americans, said the England ‘keeper, turned up wearing sombreros and smoking cigars and only touched the ball six times in the whole game.

Walter, who has a gently amusing manner these days, had a simple response. “To win 1-0,” he pointed out, “you only need to touch it once.”

Walter is a competitor to his fingertips. He spent his life as a soccer coach, his two sons became NFL stars (and each won two Superbowl rings) and his grandson, Dieter, has the potential to make it as a soccer player.

He is looking forward to the rematch between England and the US and, while he concedes that England will once again be favourites, he warns that if he were an England fan he “wouldn’t want to play the United States”, which these days is a tactically-sound, technically-proficient professional unit.

He offers this thought too. “I’m going to rub one thing in though and I never even thought of this.

“It’s taken England 60 years to have the opportunity to tie up this series in World Cup finals play. We’ve led them 1-0 for 60 years.”

Invention

The 1950 game is a part of sporting history now – and urban myths swirl around the memories.

You may have heard that some English newspapers reported the result as 10-1 to England because they assumed there was some sort of typing error on the wire services when they reported it was 1-0 to the US. As far as we can discover, that’s just not true.

And the story that the following day’s English newspapers appeared with black edges like funeral cards also appears to be an invention.

Not many games can claim to make a lasting impact, but England played in blue shirts that day in the mining town of Belo Horizonte – and after the defeat they never played in blue again, the tale goes. (In fact, England played once more in royal blue in Peru in 1959, a friendly the English lost 4-1.)

The game made an impact on American popular culture too – a movie about five years ago celebrates it as The Game of Their Lives.

But the film is curiously wooden and cliched. Walter doesn’t like it much, although if you’re English you might be amused by the way in which players like the modest Mortensen – a working-class Geordie – are portrayed as sneering toffs.

Football’s lesson

If you’re a football fan from anywhere except England or the US you will probably remember the World Cup of 1950 for the final between the favourites Brazil and Uruguay, which was played before the biggest sporting crowd of all time – 199,954 fans crowded into the Maracana stadium.

Those who were there in Rio de Janeiro remembered it for the eerie silence that descended as it became clear that Uruguay were going to have the temerity to win.

But if you are English or American, then the lesson you take away will be different – it is that anything can happen in football.

As England once again prepare to take the field as favourites against the United States, it is a lesson worth remembering.

Leave a Reply